Transat - Repairs off the beaten track and another lesson learned - part 1

- Ana

- Mar 11, 2023

- 8 min read

When we left Cascais in Portugal, we knew we would be leaving the comfort of knowing parts could be easily sourced, albeit with some work and headache due to our nomadic circumstances. We were now leaving the comfort zone of Europe and the Mediterranean where even in Tunisia vital parts were just a short quick flight away if needed.

The Madeira archipelago, part of Portugal and Europe, was still a haven to receive parts, although with additional delays and extra shipping costs.

The Canaries, more specifically Las Palmas was the last haven for boat repairs and spares. Being an important sailing destination in itself and also the jumping-off point for the majority of Atlantic crossings and the last big ports for those that carry further afield before their crossing, meaning it is well stocked with all we could need, and all that had not been accomplished before arriving here (in our case this was the whisker pole, as this was the only place that had the parts we needed in stock).

When we left for the Cape Verde archipelago we thought we were well prepared and well stocked, we knew that thinking we could source any parts for repairs in Cape Verde was just silly.

We would confirm this in Mindelo, although thankfully we had no issues to be solved. We simply didn’t see any shops that would have tools or bits and pieces (even if not marine grade) that could be fashioned into a repair if needed.

In Mindelo, our only issue was provisioning, because clearly, we had not stocked up on enough snacks, and treat food. Maybe due to the holiday season, we were confronted with a very reduced availability of fresh products, not to even mention variety. It was also the first place we saw rationing of eggs (we had experienced rationing of food sales during the first Covid lockdown in Tunisia, so this was not our first rodeo circumventing the situation).

When we departed Mindelo, Cape Verde we knew that for 10-15 days (our estimated duration of passage) we would be isolated from any support that didn’t involve a mayday and abandoning ship. At least during the crossing from the Canaries to Cape Verde, we had seen other sailing vessels on AIS, a few fishing boats and even cargo vessels that could render some assistance.

From Cape Verde, until we reached Brazil we would be all alone, left to our own devices, skills and resilience in the big blue "desert” that is the Atlantic Ocean. Except for the distant Japanese fishing fleet that would not be interested in us at all.

Despite our preparation efforts, our crossing was a challenging one marked by a couple of breakages that would require our attention in Brazil.

You can read about our crossing challenges and breakages in the following links:

Given the importance of these systems the eventuality of these breakages was something we had prepared for, what we had not thought about was how and where would we be able to do repairs if anything broke.

Understandably, our morale had been shaken with the first breakage and sank to unthinkable levels (mostly due to our exhaustion) with the second breakage, making our crossing very challenging.

With our jury rig sorted our priority was arriving at our first stop, Fernando de Noronha, still two days' distance from Brazil's mainland where we could sleep properly and rest before thinking about what we needed to do. At this point, we were already in direct contact with our Brazilian sailor friends Rita and Rubens to get their advice on where was it best for us to go for repairs.

We knew that once we arrived at Fernando de Noronha archipelago off the coast of Brazil all we could do was tidy up the mess of toolboxes, bits and pieces that were required to build our jury rig structure for the Hydrovane tiller pilot, do some troubleshooting, rearrangement of the 240v system and start researching how could we correctly diagnose and repair the autopilot.

After all, Fernando de Noronha is definitely off the beaten track when it comes to repairing facilities and supplies, despite being on the path of becoming a huge tourist destination (apparently the last few years have already seen a boom in this industry on the island).

What we did not expect was not to be able to buy a SIM card on the island and have very limited access to the internet. That was incredibly limiting to us, which meant the necessary research regarding our repairs would have to wait until we arrived in mainland Brazil.

Our friends advised us that our best chance to get the pilot fixed was in Salvador where there are a few good technicians, but even then, if any parts had to be ordered that this could be a problem, but the sail from the archipelago directly to Salvador would be a long one beating to the wind and sea. We decided to go straight to Recife, two days away from Fernando de Noronha, where we would need to complete our check-in formalities and from there hop down the coast until we reached Salvador, taking the opportunity to relax a bit and enjoy life.

Once we got to Salvador we immediately focused our attention on the pilot issue.

Through the recommended technician (that guided us remotely via WhatsApp while he was actually on a job in Europe and not in Brazil) we discovered that ordering any parts from Lewmar or other suppliers would imply 30-60 days being held by Customs and paying most likely 100% duty. We had not yet checked the price of a new autopilot, but for sure it was not cheap, and the chance of 100% duty seemed eye-watering.

Finding out the limitations of Brazil was a real slap in the face.

Something we had not expected.

Such a big country with such big modern cities, with a reasonable sailing community and a reasonably big boating community this difficulty in sourcing out parts was something we had not expected.

With the technicians help, we learned quite a bit about how our system works and how to do some diagnostic tests, but we did not solve the problem, although, for a brief moment, we thought the problem was a very simple one it turned out to be a major issue.

The Dream steering is a chain and cable driven system leading to the quadrant. Via a secondary set of chains, the main assembly connects to a Lewmar drive unit autopilot. The drive unit is installed in the lazerette right in front of the main helm station, and with our arrival to Salvador, it was time to start trying to identify the actual problem of the autopilot and see if it was possible to repair.

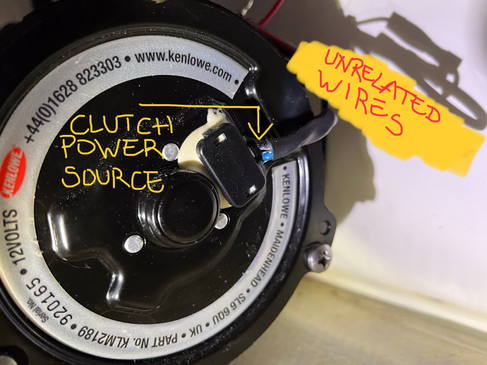

The Lewmar drive unit has two sources of power, one for the motor and another for the clutch.

Given that we could hear the motor running and it sounded as always (noisy as hell), we had already established the problem was not in that section of the equipment, so the first step was to check if the clutch was mechanically sound or if the problem was electrical.

We disconnected the clutch from the boat power source and connected it to our small portable 12v battery (a very handy thing to have onboard ready to power anything from a spare Chartplotter that can be used in the dinghy to a portable high capacity bilge pump, etc.). By doing that we should be able to see if the clutch engaged or not once we activated the autopilot as it would grab the helm.

A bit to our relief, the moment we engaged the autopilot, we felt the clutch grab the helm, it was easy to confirm the pilot was indeed engaged as the helm was no longer loose and turning it by hand was not possible. The next step was to press starboard or port 10 degrees or more to see if the autopilot would try to turn the steering, although we were stationary at anchor the helm should turn, which it did. This meant the problem was not mechanical like a melted pulley, gear, etc. the problem was electrical.

Now, we needed to test the power source via the Course Computer (Raymarine).

We opened the unit and checked the wires at the clutch connector, nothing was loose or burnt, so we kept chasing the wires further "upstream".

Right next to the Course Computer, we identified two small boxes that are connected to the power source between the 12v house bus bar and the Course Computer.

One is a double fuse holder the other is a resistor.

The problem was immediately identified as we opened the fuse holder. The 5A fuse that protects the clutch system was blown!

We quickly grabbed a spare fuse and tried to try it out, and it seemed the autopilot was again working.

For a few days, we felt relieved and, at the same time, silly for not having identified the blown fuse at sea. It felt like the sun was back shining on us, and a big weight had been lifted from our chests.

A weight that had been present since the 5th day of the Atlantic crossing, nearly a month before, and that was impacting our ability to enjoy this new country.

After a couple of hours motoring in the bay of Todos os Santos and all seemed ok, but a few days later when we were on our way further south to meet up with our friends, the autopilot blew the fuse again after maybe 3 hours of use in relatively calm sea and no wind.

To our despair, the autopilot had overheated again!

We hand steered for a few hours to the only place we could anchor for the night (near Morro de S.Paulo/Gamboa, a river entrance) between Salvador and our destination, with an increasingly annoying swell as we came closer to the river entrance.

In the protection of the anchorage where we would stay for the night, we reassembled the tiller pilot, and realigned the sprocket (the chain that connects the autopilot to the helm) just in case it had become misaligned during the long Atlantic crossing causing extra undue friction causing the system to overheat, replaced the fuse again and decided the following day we needed to test the system again to understand why the fuse was blowing and where was the problem.

The next morning we made our way out of the river entrance anchorage. The plan was to monitor the autopilot closely. Armed with the clamp-on voltmeter, we were checking the power draw in all the cables just before the Course Computer, the temperature of the wires, the resistor and the autopilot unit itself every 30 minutes or so.

Whilst at anchor the power consumption of the unit seemed to be within the parameters of the specifications, but now that we were underway the unit was drawing nearly 1A more than it should. This sounds minimal, but if there is no mechanical reason to justify the extra power draw (extra friction, for example) this indicates there is an electrical flaw.

At the same time, we noticed the clutch side of the autopilot was fast warming up, while the motor side was warming up slowly and only because of the proximity to the much hotter clutch assembly.

After close to 3h of use the clutch was hot, and the fuse eventually blew.

We switched to the tiller pilot and completed our day passage, knowing now something of electrical nature was not well in the clutch assembly.

The dark cloud had rolled back over our heads, and we knew we had an urgent problem to be solved before we could start exploring this country or before we had to start making our way out to another country.

***In the spirit of sharing our dreams and experiences we have shared this blog post in the NOFOREIGNLAND.COM website sailors community.

Comments